In my last post, I introduced an Agrément Certificate issued by the British Board of Agrément (BBA) to Sto in 1995 for an External Wall Insulation System. Examining the version of the system with combustible Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) insulation, I first questioned the basis on which it had been granted a Class 0 Reaction to Fire rating (Detail Sheet 2):

Then I expressed alarm that the BBA granted approval for the system to be used at any height:

in apparent direct contravention of the restriction, introduced into Approved Document B in 1992, of the use of combustible insulation to buildings of 20 metres or lower:

I sent an email to the BBA on 15 April to ask whether they now believed the Certificate was issued in error, but have not so far received a reply.

In this post, I examine the one remaining sub-section of Section 4 of the Sto certificate, dealing with fire:

The map indicates that the application is to Scotland only. Section 2 lays out the Regulations and Technical Standards which the BBA believes the Sto system can satisfy, or contribute to satisfying:

Regulation 12(1) of the Building Standards (Scotland) Regulations 1990 (as amended) laid out the overall objectives of the Structural Fire Precautions:

The statutory Building Regulations were accompanied by Technical Standards, with which compliance was compulsory, as stipulated in Regulation 9(1) of the statute:

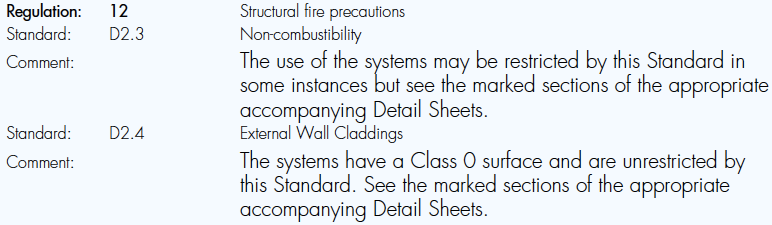

The BBA listed two Technical Standards as relevant to the satisfaction of Regulation 12:

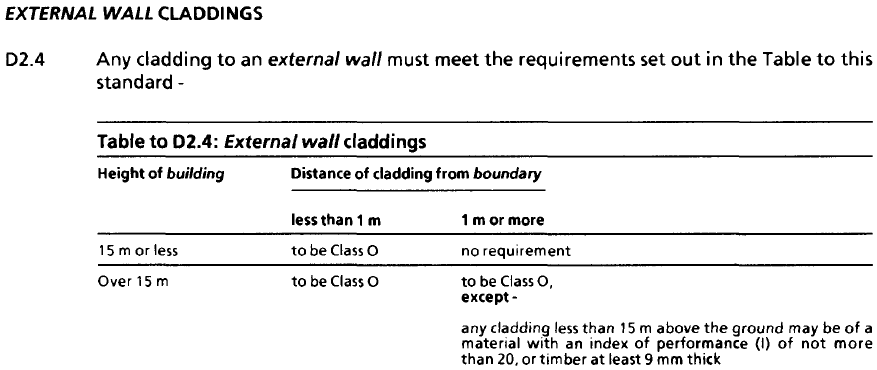

Taking the second of these first, Technical Standard D2.4 required that, for buildings over 15 metres high, cladding above that 15 metre height should be Class O, with a less stringent requirement, and a concession for timber, for cladding below 15 metres. Also, cladding on buildings less than 1 metre from a boundary had to be Class O:

Since the Sto system had a Class 0 surface, according to the BBA:

and since the BBA’s Class 0 (zero) is equivalent here to the Scottish Class O (capital o), 1 it could thus be used on buildings of any height and boundary distance, and so was ‘unrestricted by this Standard’:

In Scotland, however, there was a further standard which could impinge upon and restrict the use of a cladding system:

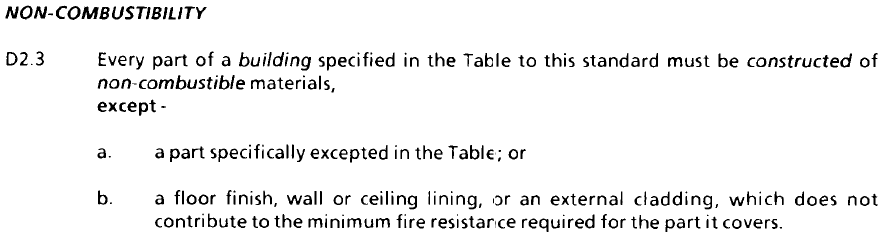

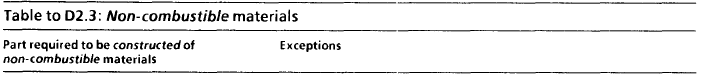

Technical Standard D2.3 required certain parts of a building to be built of non-combustible materials, although with certain concessions:

The only non-combustibility requirement for external walls was for those on the boundary or within 1 metre of the boundary:

………………

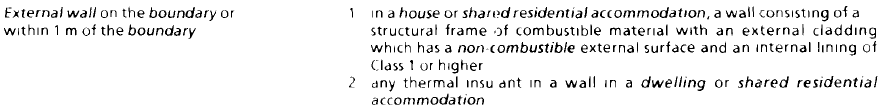

If the structural frame of the external wall was non-combustible then there would be two possibilities. If it met the fire resistance requirements on its own then, according to D2.3(b), the cladding would not have to be constructed out of non-combustible materials:

If it did not meet the fire resistance requirements on its own, then the cladding would have to be non-combustible, but with an exemption for the insulation:

…………………………..

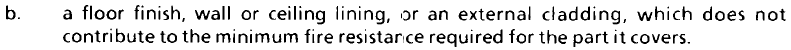

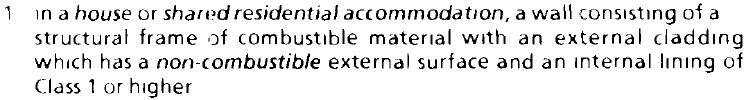

But if the structural frame of the external wall of a house or shared residential accommodation was made of combustible materials, then it had to have an internal lining of Class 1 or higher, and in addition a cladding with a non-combustible external surface:

……………………………..

To be classified as non-combustible under the Technical Standards, a material had to be certified as such according to BS 476 part 4 (a 750° C furnace test standard). A concession was made for plasterboard (Appendix to Part D, section 5):

The point I want to take from this is that in some circumstances there is a requirement for the external surface of the cladding to be non-combustible. For a rendered EPS system, this external surface may I think be taken as the render.

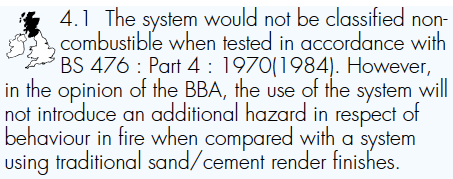

We may now return to Section 4.1 of the certificate:

The reference to non-combustibility shows that this sub-section must relate to Standard D2.3, ‘non-combustibility’, rather than to D2.4, ‘External Wall Claddings’, which has no non-combustibility requirement.

The BBA accept that the systems may be restricted by this standard ‘in some instances’:

What would these instances be? The systems are not non-combustible. Where the building is further than 1 metre from the boundary there would be no restriction. But where the building is on the boundary or within 1 metre of the boundary, then there would I think be two circumstances in which these Sto systems could not be used, according to the Technical Standards:

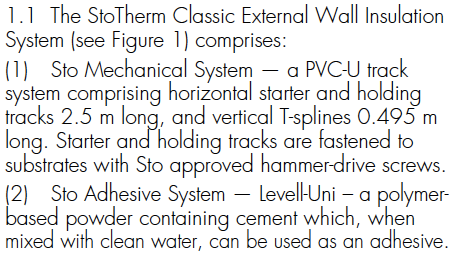

1) Where the structural wall was non-combustible, but did not meet the fire resistance requirements on its own, then the whole cladding system, apart from the insulation, would have to be non-combustible. The systems could fail to meet this requirement on more grounds than one. The EPS version, for example, had a PVC track system and a polymer-based adhesive, both on the wall side of the insulation boards:

In addition, as I described in an added section to my last post, all three versions of the Sto system use one of three renders, all of which have an organic base, either acrylic or silicone:

Both acrylic and silicone would certainly burn in the 750° C furnace of BS 476 part 4, and I think there can be little doubt that all three products would fail to meet the criteria for non-combustibility of that test standard.

2) Where a house or shared residential accommodation had an external wall constructed of combustible material, the cladding would have to have a non-combustible external surface. Since the render was combustible, none of these systems could be used, according to the Technical Standards.

If we look another time at section 4.1 of the certificate:

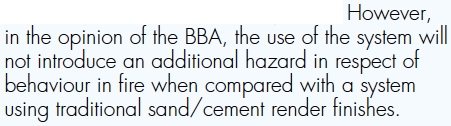

we can see that the comparison is made with systems that have a non-combustible sand/cement render finish, rather than those which are non-combustible throughout (apart from the insulation). It seems clear then that it is the second circumstance in which the Sto systems would be prohibited that is in view here, because it is in this second circumstance that it is the combustible ‘external surface’, the combustible render, that prevents them being used.

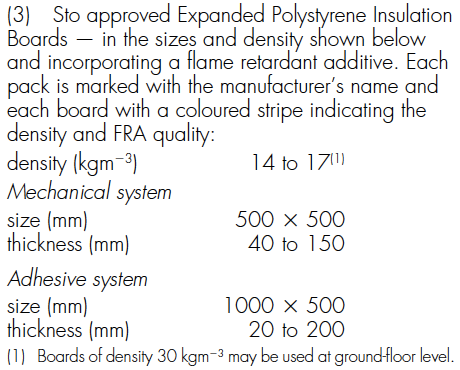

The BBA, to its shame it seems to me, gives its ‘opinion’ that using a combustible render rather than a non-combustible render would not introduce an additional fire hazard. Oh really? Why not? The render was protecting EPS board of up to 20 centimetres thickness:

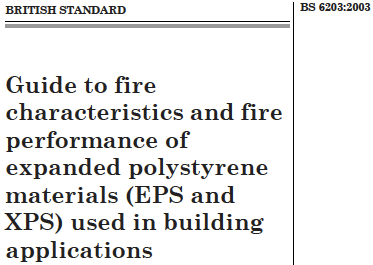

British Standard BS 6203 (2003):

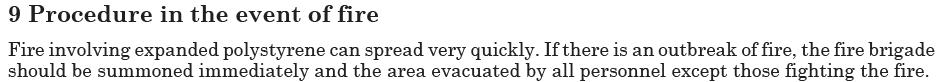

observes that EPS fires can ‘spread very quickly’, and the area should be evacuated by all except firefighters:

Flame retardant additives can protect EPS against ignition by small heat sources but not by large ones:

When EPS is attacked by a larger heat source, the addition of flame retardant results in a moderate increase in time to ignition, and decrease in rate of heat release, but little or no reduction in total heat release:

On 21 April 2005, a fire started on the second floor of a seven storey apartment building in Germany, broke out of a window, and spread up the rendered EPS facade, reaching the top of the building in only twenty minutes (p. 25):

Two people died. On 15 August 2009, in Miskolc, Hungary, a fire started in a kitchen on the 6th floor and spread up the rendered EPS to the top of the 10-storey building, resulting in three fatalities:

On 14 November 2010, a fire spread rapidly up the rendered EPS facade (p. 24) of a residential building in Dijon, France, resulting in seven deaths:

In 2012, a fire spread from the ground floor of a rendered EPS facade in Târgu Mureș, Romania, to the top floors in just ten minutes according to witness statements:

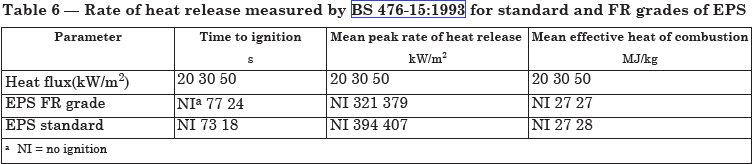

It is clear from the above examples that rendered EPS facade fires are potentially very dangerous indeed. But how much difference does it make whether the render is combustible or not? Possible stages by which a window break-out fire may penetrate to the EPS insulation are illustrated in a Croatian academic paper. In phase two the insulation begins to melt and hollow out:

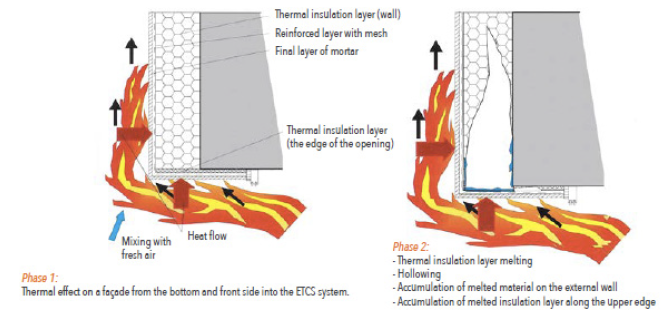

In phases 3 and 4 the render comes under stress from hot gases and molten material, and can finally come away, allowing the flame to penetrate behind it:

Among the features of Phase 3 is listed the ‘Burnout of organic plaster’. That is to say, if the ‘plaster’ is organic, then it may fail by burning through. This is only common sense, after all. Since this mode of failure is specific to organic render, does its use not therefore present an ‘additional hazard’?

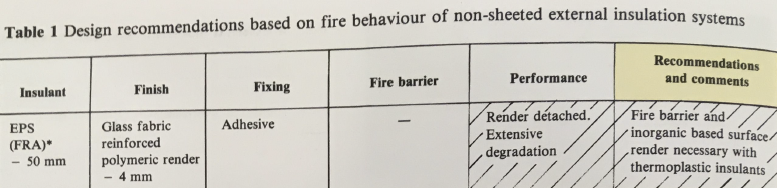

As I pointed out in my last post, BR 135 (1988) ‘Fire performance of external thermal insulation for walls of multi-storey buildings’ gave a specific warning, based on the results of a large-scale test, against the use of organic render with EPS insulation:

In the tested system, with 50 mm of flame retardant EPS and a polymeric render, the render became detached and there was ‘extensive degradation’ of the system. The BRE advised that it was necessary to use ‘inorganic based surface render’ with thermoplastic insulants. When this improvement was made, in addition to the provision of a fire barrier at each storey, there was only limited degradation of the system:

The BBA must have known this report. How then could they say that the use of an organic render rather than an inorganic one would introduce no additional hazard? Did they only read the summary recommendations and fail to study the more detailed recommendations contained in the table?

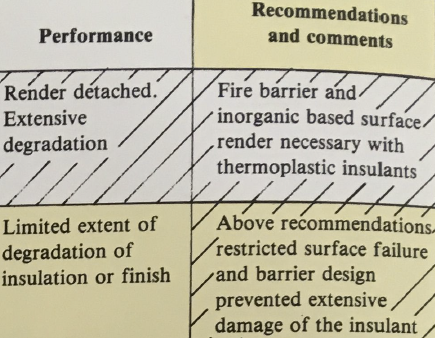

In 2010, the BRE tested four different rendered EPS systems to BS 8414-1, and three of them also to a draft German test standard, DIN 4102-20. One system employed inorganic render, while the others used organic render. Both tests of the system with inorganic render resulted in a pass (to BR 135 in the case of the BS 8414 test). All five tests with organic render resulted in a fail:

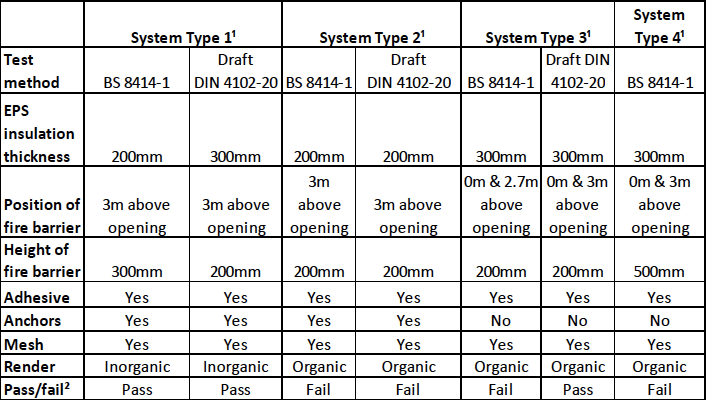

Photographs during and after the test of the system with inorganic render:

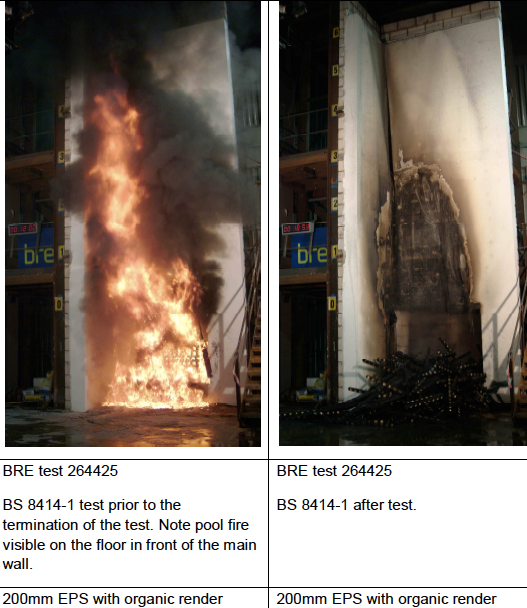

may be contrasted with an otherwise similar (although admittedly not identical) system with organic render: 2

The BRE drew out the difference in performance between the system with inorganic render and those with organic render:

How then did the BBA reach its opinion that the use of organic render rather than a non-combustible sand/cement render would not introduce any additional hazard?

Had the BBA carried out tests that brought them to this conclusion? Had they performed calculations? Was a report written to justify their reasoning? Or was it perhaps wishful thinking? What do you say, BBA?

An assault on the law of the land?

What was the purpose of section 4.1 of the Sto certificate? Did the BBA just think that the reader would be interested to know their opinion about render? Presumably not. They were giving their opinion that where inorganic render was required by the Scottish Building Regulations, use of the Sto product would introduce no additional hazard. Surely that is tantamount to giving their approval to such use. Why else would they say it?

It seems to me that what the BBA is saying is that where non-combustible render is required, that is when a house or shared residential accommodation is on the boundary or within 1 metre of the boundary, and has a combustible structural frame, then this product may be used, even though it falls short of Technical Standard D2.3.

But to use it would mean breaking the law in Scotland, since compliance with the Technical Standards was obligatory at that time under Regulation 9(1) of the statutory Building Standards (Scotland) Regulations 1990 (as amended). And this amounts to an assault on the law of the land in Scotland, so far as I can see.

Andrew Chapman

Notes:

- The only difference between the Scottish definition and the Approved Document definition was that the latter, oddly, seemed to allow, as it still does now, a material to achieve Class 0 without testing if the surface of a composite product was composed throughout of materials of limited combustibility. In this case, the surface of the system was combustible, so this potential route to compliance was not open to it. The requirements for achieving Class 0/O by testing to BS 476 parts 6 and 7 were the same in the Approved Document as they were in the Technical Standards. ↩

- The insulation thickness is given here as 300 mm, but in Table 1, for the same test with Report number 262211, it is given as 200 mm. ↩