How did we come to be here? Did God create us out of nothing, or did we evolve from inanimate matter by natural processes? This is the question I want to address in a series of posts. Since many have been here before, and much of the ground has been worked over many times, my intention is to look in some detail at a few key issues, starting with the origin of life itself, attempting only to make a small contribution in limited fields of enquiry.

According to the dominant scientific paradigm, as expounded by Richard Dawkins for example, life began when naturally occurring substances synthesised by natural and undirected physico-chemical means into self-replicating entities. It is thought that no intelligence was involved in the first emergence of life in the universe, and indeed that there was no mind at all until more advanced organisms evolved with brains and neural networks.

the miller-urey experiment

On 15 May 1953, less than three weeks after Crick and Watson suggested the double helix molecular structure for DNA in Nature, Stanley Miller reported in Science that he had synthesised amino acids under conditions meant to simulate a possible ancient earth atmosphere:

Miller’s research had already been found worthy of a mention in the Science columns of Time Magazine the previous November. Miller’s supervisor Harold Urey, who had received the Nobel Prize in 1934 for his discovery of ‘heavy hydrogen’ (now known as deuterium), told Time (24 November 1952) that:

Miller’s research had already been found worthy of a mention in the Science columns of Time Magazine the previous November. Miller’s supervisor Harold Urey, who had received the Nobel Prize in 1934 for his discovery of ‘heavy hydrogen’ (now known as deuterium), told Time (24 November 1952) that:

Life is not a miracle … It is a natural phenomenon…

Urey believed that there would have been little or no free oxygen in the atmosphere of an early earth: 1

In the absence of oxygen, and with energy supply from the sun, organic compounds could form in the atmosphere and rain down into the ocean:

According to Time, Urey theorised that in the course of a billion years of chemical evolution:

According to Time, Urey theorised that in the course of a billion years of chemical evolution:

the blind forces of chemical attraction

could:

accidentally create a single molecule

which has the ability to:

absorb other molecules and create a replica of itself.

Such a self-replicating molecule could be considered to be alive, and would multiply and differentiate, according to Urey’s hypothesis (as represented by Time):

One of these ‘hungry molecules’ could then learn to photosynthesise, releasing oxygen into the atmosphere, and a successor to breathe, initiating ‘the full stream of evolution’:

Urey expressed hope that the experimental work of one of his students (Miller) could provide evidence in support of his grand theory:

media reaction

In an account (p. 237) published in 1974, 2 Miller recalled being surprised by the level of media interest in the success of his experiment:

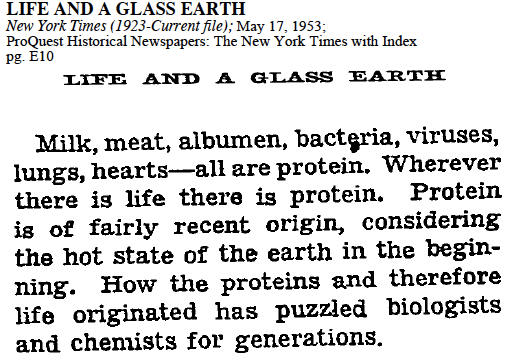

A search in the New York Times Historical Archive (1851-2103) yielded only one article, published on 17 May 1953, two days after the publication of Miller’s results in Science, and entitled ‘Life and a Glass Earth’. A striking feature of the article is its identification of the origin of life with the origin of protein:

How the proteins and therefore life originated…

It is understandable that a journalist in 1953 might not have seen the full significance of DNA on 17 May 1953, still two weeks before Crick and Watson had published in Nature their second paper (30 May 1953), on the ‘Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid’. Indeed, until Oswald Avery and his colleagues provided evidence in 1944 that DNA could induce transformation in bacteria, it was generally held that gene specificity had its basis in protein and not in DNA. 3 It took several years and much confirming evidence before the new view was accepted, and even in 1955 the geneticist Richard Goldschmidt was still of the opinion that ‘the DNA molecule is the scaffold which keeps the proteinic gene material in place for its reduplication’. 4

Our journalist went on to point out the influence of the Soviet biochemist Alexander Oparin on Urey and Miller’s theoretical model:

Miller and Urey themselves, in a 1959 paper in Science, acknowledged that:

Many of our modern ideas on the origin of life stem from Oparin

So who was Oparin?

Oparin

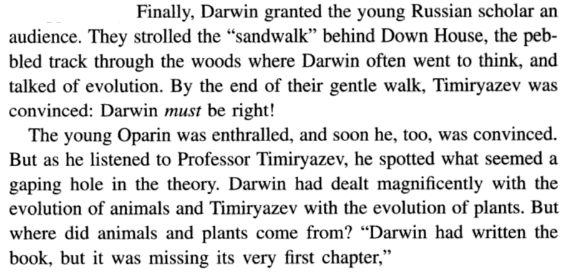

Alexander Oparin (1894-1980) was a Russian biochemist who prospered under Stalin’s rule, becoming director of the Institute of Biochemistry in 1946. 5 He studied plant physiology at Moscow State University, where he had been influenced by the plant physiologist K. A. Timiryazev (1843-1920), who had published ‘An outline of Darwin’s theory’ in Russian in 1865, only six years after the publication of Origin of the Species, and had continued to promote Darwinism in Russia until at least 1912, when he authored a short article on Darwin in a Russian encyclopedia.

1912 was also the year that Oparin made his first visit as a prospective student to Moscow State University, at least according to an account he gave at the University of California Los Angeles in 1976, as recalled (p. 111 ff) by his host William Schopf.  Oparin said that he had attended a lecture by Timiryazev, who had recounted – according to Oparin – how he became a Darwinist during a conversation with Darwin himself at Down House. The visit was in 1877, according to Timiryazev’s written account (which must surely be considered the more reliable one), and he didn’t stay in a pub for a week (p. 112) waiting to see Darwin, as the account via Oparin and Schopf has it, but made the visit from London in one day. If this detail is wrong, then one may doubt also that Timiryazev became a Darwinist on that day, twelve years after writing a book about Darwinism.

Oparin said that he had attended a lecture by Timiryazev, who had recounted – according to Oparin – how he became a Darwinist during a conversation with Darwin himself at Down House. The visit was in 1877, according to Timiryazev’s written account (which must surely be considered the more reliable one), and he didn’t stay in a pub for a week (p. 112) waiting to see Darwin, as the account via Oparin and Schopf has it, but made the visit from London in one day. If this detail is wrong, then one may doubt also that Timiryazev became a Darwinist on that day, twelve years after writing a book about Darwinism.

Oparin told the UCLA students that as he listened to Timiryazev’s presentation of Darwin’s theory on that day, he himself became a Darwinist in a sudden conversion, as Timiryazev supposedly had before him, but then immediately realised that Darwin’s book was:

missing its very first chapter

The evolution of plants and animals had been explained, Oparin believed, but where did the plants and animals come from? How did life itself begin? He devoted the rest of his life to trying to answer this question, or so at least he told it:

While the details of the narrative may be suspect, there is no reason to doubt that Oparin found himself confronted, as many other evolutionists have been since 1859, by what a historian of the spontaneous generation controversy called ‘the dilemma of abiogenesis’. 6

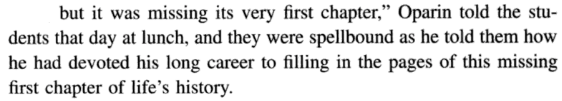

The Oxford English Dictionary helpfully gives two meanings of ‘abiogenesis’:

The first relates to organisms arising from inanimate matter today, rather than by descent from progenitors; the second to virtually the same process in the distant past. The dilemma arose from two concurrent developments in science. First, it came to be generally recognised, contrary to Aristotle and some other Greek thinkers, that the earth had not existed from all eternity, but had had a beginning, with the consequence that life also had had a beginning. Moreover, according to the leading naturalistic cosmogony of the nineteenth century, the earth had once been too hot to sustain life, sharpening the perception that there must have been a starting-point to life on earth.

Second, again contrary to Aristotle and to much popular belief, scientific experiment demonstrated in the nineteenth century that the spontaneous generation of living things from dead organic matter was a chimera. Life comes from life, and does not spring forth from inanimate matter. If not from organic materials, then how much more not from inorganic.

darwin’s solution

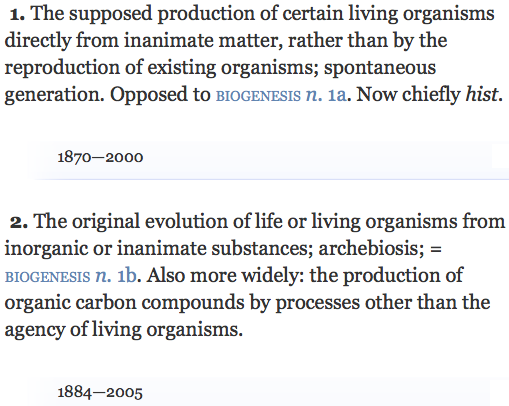

What Oparin called the ‘first chapter’ of the theory of biological evolution was not in fact entirely missing from Darwin’s Origin of the Species. In the first edition of 24 November 1859 he proposed that all animals and plants had been descended from at most four or five ancestors (p. 484):

What Oparin called the ‘first chapter’ of the theory of biological evolution was not in fact entirely missing from Darwin’s Origin of the Species. In the first edition of 24 November 1859 he proposed that all animals and plants had been descended from at most four or five ancestors (p. 484):

and probably from just one prototype, one primordial form,

into which life was first breathed:

……

and a similar expression is used in the final sentence of the book (p. 490):

In the second edition published less than seven weeks later on 7 January 1860, 7 Darwin added in both places that life was first breathed (pp 484, 490)

by the creator:

……

In the third and more substantially revised edition, published in April 1861, the idea of life being breathed into the first creature was removed in one place (p. 518):

but retained in the other (p. 525):

Darwin on spontaneous generation

In supplementary material added to the first authorised American edition, published in May 1860, 8 Darwin rejected spontaneous generation categorically:

He may possibly have been influenced by one or more of Pasteur’s series of five papers on the subject (published between February 1860 and January 1861). 9 Pasteur’s experiments were with dead organic material, but his results could reasonably be expected to apply all the more to inorganic substances.

Darwin on special creation

Turning his attention to those who believed in the individual special creation of countless species, Darwin asked in all three editions whether they really believed that living tissue was formed at God’s command (1st edition, p. 483):

Darwin’s critics were not slow to point out the apparent inconsistency, or tension at the least, between this rhetorical question aimed at those who believed in the special creation of many species, and his own stated belief in the special creation of one or a few species.  Richard Owen, the anatomist and palaeontologist, and superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum, took aim at this weak point in his review of Origin of Species in the Edinburgh Review of April 1860. Having quoted from page 484 of the first edition what he calls Darwin’s ‘scriptural phrase’ about life being breathed into the first primordial form, Owen draws attention to Darwin’s implied criticism of those who believed in something similar:

Richard Owen, the anatomist and palaeontologist, and superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum, took aim at this weak point in his review of Origin of Species in the Edinburgh Review of April 1860. Having quoted from page 484 of the first edition what he calls Darwin’s ‘scriptural phrase’ about life being breathed into the first primordial form, Owen draws attention to Darwin’s implied criticism of those who believed in something similar:

No doubt mindful of the criticism, Darwin, in his third edition, inserted an admission that, in the ‘present state of science’, the questions he had asked of the special creationists could not be answered by those like himself who believed in the creation of one or a few forms:

on the horns of a dilemma

We may leave Darwin for now, caught on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, science provided no support for the notion that living organisms could be produced from inorganic substances by natural processes. On the other, he found it very hard to believe that God would bring forth plants and animals by decree. So he contented himself with continuing to propose, in subsequent editions of Origin of Species, that the Creator had breathed life into one or a few forms. His private position was different, as I intend to describe in my next post.

Andrew Chapman

Notes:

- See also Harold C Urey, ‘On the Chemical History of the Earth and the Origin of Life’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 38, 1952, pp 351-363, at page 353. Link. ↩

- S. Miller, ‘The First Laboratory Synthesis of Organic Compounds under Primitive Earth Conditions’ in Neyman, J. (1974). The heritage of Copernicus : Theories “pleasing to the mind”. Cambridge, Mass ; London: MIT Press. ↩

- Avery, O., Macleod, C., & Mccarty, M. (1944). Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types: Induction of Transformation by a Desoxyribonucleic Acid Fraction Isolated from Pneumococcus Type III. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 79(2), 137-58. Link. For the earlier view see Matthew Cobb, ‘Oswald Avery, DNA, and the transformation of biology’. Link. ↩

- See Cobb, op. cit. Goldschmidt quotation from R. Olby, ‘The Path to the Double Helix’, p. 152. Link. ↩

- Graham, L. (1973). Science and philosophy in the Soviet Union. London: Allen Lane. p. 259. Link. ↩

- Farley, J. (1977). The spontaneous generation controversy from Descartes to Oparin. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 141. ↩

- Keith A Francis, ‘Charles Darwin and the Origin of Species’ (Greenwood Press, 2007) pp. xviii, xix. Link. ↩

- Browne, Janet (2010). ‘Asa Gray and Charles Darwin: Corresponding naturalists’. Harvard Papers in Botany 15(2): 209- 220. p. 8 of online edition. ↩

- For these dates see Roll-Hansen, N. (1979). Experimental method and spontaneous generation: The controversy between Pasteur and Pouchet, 1859–64. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 34(3), 273-92. at p. 283. Link. ↩