I left off my last post halfway through an introduction to Thomas Huxley’s positive review of Origin of Species in The Times of 26 November 1859. I had found Huxley in 1854 committed to the notion of fixed archetypes, giving room for evolution of types within prescribed bounds only. In this post I find Huxley, the following year, still opposed to transmutationism, but now in the context of a broader opposition to ‘progressive development’ in both its transmutationist and creationist varieties.

On 20 April 1855, Huxley gave a lecture at the Royal Institution, taking issue with arguments for what he called ‘progressive development’: 1

He began by placing the matter at hand in the context of the historical development of palaeontology and zoology. Once it had been realised that fossils were no ‘freaks of nature’, but were the remains of ancient living things, it had become a ‘highly interesting problem’ to determine what relationship the ancient forms had to those of today:

Comparing present day organisms with those of the Palaeozoic epoch (the oldest of the three main divisions), he found that whereas the species and genera were generally different, the orders were usually the same, and the classes and sub-kingdoms always so:

Looking at the matter as a whole, he saw a ‘general uniformity’ in the operations of nature over time (p. 301):

Nevertheless, there was no doubt that living beings were different now than formerly, and moreover those of each epoch differed from those of the preceding one, so that there could be said to be a ‘succession’ of forms in time:

Huxley then appears to take for granted that there must be a law to govern that succession:

Interposing a comment here, it seems to me that if God has created the natural world, then it may have been not according to law at all, but rather according to His will. But to proceed.

One school, Huxley says, puts forward a theory of Progressive Development in which the progress of life on earth is analogous to the development of the individual creature from seed to maturity:

Two versions of the theory

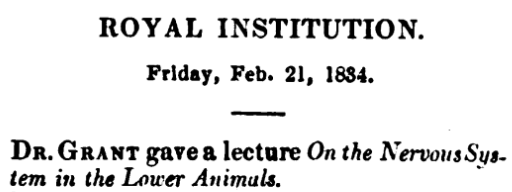

A little care needs be taken in identifying exactly which school of thought Huxley is referring to. The idea much resembles the recapitulation theory that is commonly associated with Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) and his summary of it that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’. Meckel (1781-1833) and Serres (1786-1868) had speculated that the embryos of higher animals pass through stages analogous to adult forms of lower animals. The notion was taken up by Geoffroy St Hilaire (1772-1844), and then by Robert Grant (1793-1874), who added what Adrian Desmond calls a ‘third dimension’, an historical evolutionary progression, shown in the fossil record, of higher animals succeeding lower animals by descent. 2 He was reported in the London Medical Gazette 3 as entertaining a nonprofessional audience in 1834 with the notion that the embyronic brain of man passed through tadpole, fish and crocodile brain forms:

……

Richard Owen took time in his Hunterian Lectures of May 1837 to attack this evolutionary version of the recapitulation theory: 4

Huxley’s target, however, was a different one, as becomes clear as his paper progresses.

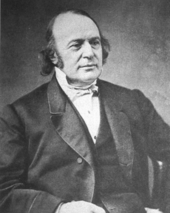

Louis Agassiz’s theory of progressive development

Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) was Professor of Natural History at the University of  Neuchâtel from 1832, where he worked on fossil fish in particular, and subsequently became Professor of Zoology and Geology at Harvard University from 1848 onwards. While he saw a progressive development in plants and animals over geologic time: 5

Neuchâtel from 1832, where he worked on fossil fish in particular, and subsequently became Professor of Zoology and Geology at Harvard University from 1848 onwards. While he saw a progressive development in plants and animals over geologic time: 5

he believed that it was through extinction and replacement, not through descent by modification:

There had been great cataclysms upon the earth’s surface, Agassiz believed, citing in 1854 the research of Élie de Beaumont, who had recently published his Notice sur les Systèmes de Montagnes (1852), in which he proposed twenty-one distinct geological periods, separated by catastrophic events, which were caused by the cooling and consequent shrinking of the earth: 6

Agassiz considered that the investigations of palaeontologists provided independent support for this theory of

periods of disappearance and renovation of organised beings on earth

sandwiched, so to say, between

great successive geological cataclysms.

But if the animals died during each cataclysm, how did they advance in complexity and organisation? The answer, according to Agassiz, was that God was outworking a plan to bring forth humankind on the earth, and created in each successive period creatures tending more nearly to human form: 7

In 1848-9, during twelve lectures on Comparative Embryology delivered at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Agassiz claimed that this progression over geological time was paralled by embryological development, as well as by the relationship between higher and lower adult forms extant in the present day. He found this ‘threefold parallelism’, as Stephen Jay Gould has called it, 8 most perfectly in the Echinoderms: 9

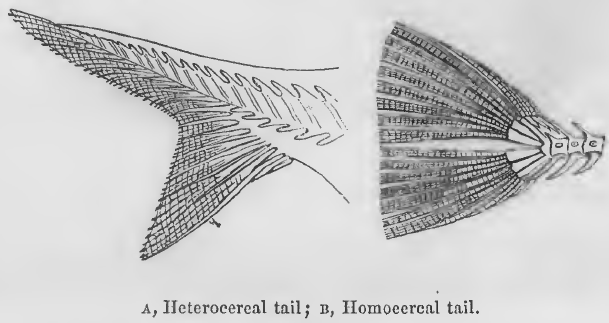

Agassiz had developed the theory by comparing the embryology, zoology and palaeontology of fish tails. Both ancient fish and modern fish embryos tended to have asymmetric ‘heterocercal’ tails, while the tails of most of the present day adult fish were ‘homocercal’: 10

Employing results of investigations by his colleague Carl Vogt also, Agassiz had presented the threefold parallelism in 1844, : 11

In 1854 William Carpenter brought out the fourth edition of his Principles of Comparative Physiology. Huxley praised it fulsomely in his Science column in the Westminster Review of January 1855, believing that it would ‘for a long time occupy a leading place among the most advance works on the subject’. 12

Carpenter presented as fact Agassiz’s observation that the tails of modern fish embryos tended to be like ancient adult forms, but not their own adult form (p. 136): 13

While accepting Agassiz’s observation, Carpenter took it as evidence of an analogy not so much between lower and higher forms as between the more general and the more specialised (p. 143):

It remained to be proved, but Carpenter believed that this could be the plan by which

the progressive evolution of the great scheme of Organic Creation

had proceeded:

He helpfully summarises the two versions of a theory of ‘progressive development’ that I have been distinguishing between. The first features successive creations, as in Agassiz’s theory, but without reference to successive extinctions (p. 133):

The second version had been advanced in Vestiges and saw lower forms being transmutated into higher forms from several distinct ‘stirpes’ (Latin: ‘root’, ‘stock’, ‘lineage’, ‘origin’ etc):

Carpenter did not believe that the fossil record, when examined closely, showed a development from lower to higher forms, and as for transmutation, the

‘facts of Physiology’

were against it, as was

‘all our experience’:

……

Huxley, in his review of Principles, reminded his readers of his consistent opposition to what he considered were premature attempts to ‘discover a definite law and order in the appearance of living beings’ on the planet: 14

He shared Carpenter’s opposition to both versions of ‘progressive development’ from lower to higher forms, but was no more taken by what was effectively a third theory of progression, this time from general to specific forms, than he was by the other two:

Huxley then devotes an entire page of the Westminster Review to a discussion of the homocercal and heterocercal fish tails. The doctrines which Carpenter had derived from Agassiz and Vogt were

totally incorrect:

‘no real parallel’

We may now resume where we left off in Huxley’s April 1855 lecture to the Royal Institution:

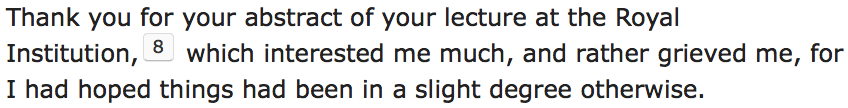

Huxley first of all takes issue with the idea of embryonic recapitulation. A mammal does not pass through a fish stage in the womb, he says. Rather both fish and mammal pass through a common Vertebrate form, and subsequently diverge:

In this, like Carpenter, he was following von Baer, who in 1828 had described a process of embryonic development from early common forms to more specialized adult forms. 15 Unlike Carpenter, Huxley did not see an analogy between such a progression in the growing embryo, and a corresponding development from general to specific in successive forms of life on earth. To demonstrate his point he presented an alternative viewpoint on homocercal and heterocercal fish tails, claiming that the whole debate on Progressive Development hinged on this one point:

He argued, first, that the living Coregonus (a genus in the salmon family) examined by Vogt were not truly homocercal in their adult form, but ‘to all intents and puposes’ heterocercal. Second, the tail was actually homocercal at an early stage of development and, moreover, it was generally true that homocercality was the younger, and heterocercality the older condition (p. 303):

In conclusion, the supposed parallel between the development of the embryo, and a progression of forms of life on earth over geological time, was an illusion, with the argument from fish tails in particular being based on a mistake:

Darwin’s reaction

Darwin read this abstract of Huxley’s lecture at the Royal Institution, and in a letter of 10 June 1855, expressed his disappointment at its findings:

Darwin’s Sketch of 1842 and Essay of 1844 had shown clear signs of being informed by von Baer’s embryology, whether from the original Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere (1828), or from articles in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal (1836-7), or from the first or second edition of Carpenter’s physiology textbook (1839, 1841). 16 Animals of widely separated type share the same common embryonic plan at an early stage, but then branch off down separate paths of development: 17

Darwin rejects the recapitulation theory that higher animals pass through the states of lower animals in their embryological development. He does say, however, that the adult lower animal may be closer than the adult higher animal to the embryonic common form:

In the Origin of Species (1859), Darwin refers to Agassiz’s theory that ancient adult forms had some resemblance to modern embryonic forms, and fully expected that the theory would be proven: 18

He comes back to the subject in his section on embryology, expressing a hope rather than an expectation: 19

Since Darwin expressed disappointment in his letter of 1855 at Huxley’s attempted refutation of Agassiz’s evidence and theory, it seems probable that he was already by then hoping that the theory would be established. Huxley was opposed to both successive creationist and transmutationist theories of progressive development. Darwin was so much in favour of progressive development, that he was willing to find support for it in a theory that was based on creationist principles, and which rejected transmutation.

The following year, 1856, Huxley, began to entertain progressive development through the transmutation of species. In my next post I intend to investigate the reasons and rationale for his change of mind.

Andrew Chapman

Notes:

- T. H. Huxley, ‘Scientific Memoirs’, Vol. I (London: Macmillan, 1898) 300-304. Link. ↩

- Desmond, A. (1989). The politics of evolution : Morphology, medicine, and reform in radical London. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 88. Link. ↩

- 1833-34, Vol. 13, p. 927. Link. ↩

- Quoted in Desmond, Politics, p. 346. ↩

- Agassiz, Louis & Gould, A. A. ‘Principles of Zoology‘, rev. ed., Boston: Gould & Lincoln, 1851. p. 237-8. Link. ↩

- Louis Agassiz, ‘The primitive diversity and number of animals in geological times’, The American journal of science and arts. ser.2, v.17 (1854) p. 314. Élie de Beaumont, J. (1852). Notice sur les systèmes de montagnes. Paris. de Beaumont’s theory was outlined at length and criticised by William Hopkins in his 1853 Presidential Address to the Geological Society of London. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 1, 1853, from p. xxviii to p. xc. Link. The twenty-one systems are listed at page xli. ↩

- Agassiz & Gould, Principles, 238. ↩

- Gould, S. (1977). Ontogeny and phylogeny. Cambridge, Mass ; London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 66. Link. ↩

- Agassiz, Louis. 1849. Twelve lectures on comparative embryology, delivered before the Lowell Institute, in Boston, December and January, 1848-9. p. 26. Link. ↩

- W. B. Carpenter, ‘Principles of Comparative Physiology’ 4th ed., (Philadelphia: Blanchard, 1854) p. 136. The drawing is Figure 78 on that page. Link. ↩

- Agassiz, L. (1844). Monographie des poissons fossiles du vieux grès rouge. Neuchâtel: Imp. de H. Nicolet; p. xxvi. Link. English translation in Dov Ospovat, The influence of Karl Ernst von Baer’s embryology, 1828–1859: A reappraisal in light of Richard Owen’s and William B. Carpenter’s “Palaeontological application of ‘von Baer’s law’”. (1976). Journal of the History of Biology, 9(1), 1-28, p. 15. Link. ↩

- Westminster Review, New Series, Vol. VII, January and April 1855, p. 241. Link. ↩

- Carpenter, Principles, 136. ↩

- Westminster Review, January 1855, 243. ↩

- von Baer, K. E., ‘On the development of Animals, with Observations and Reflections‘, whose Fifth Scholium is translated in Huxley, T. H., ‘Scientific Memoirs, selected from the Transactions of Foreign Academies of Science and from Foreign Journals‘, (London: Taylor & Francis, 1853). See page 214 and point 1, for example. Ospovat, von Baer, 5-6. ↩

- For the dissemination of von Baer’s theory see Dov Ospovat, ‘The Influence of Karl Ernst von Baer’s Embryology, 1828-1859: A Reappraisal in Light of Richard Owen’s and William B. Carpenter’s “Palaeontological Application of ‘Von Baer’s Law'”‘, Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Spring, 1976), pp 1-28; Martin Barry, “On the Unity of Structure in the Animal Kingdom,” Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, 22 (1836-1837), 116-141, 345-364; William B. Carpenter, Principles of General and Comparative Physiology (London: John Churchill, 1839), pp. 169-172; 2nded. (1841), pp. 194-198. ↩

- Darwin, Charles Robert, & Darwin, Francis. (1909). The foundations of The origin of species, two essays written in 1842 and 1844, ed. by F. Darwin. Cambridge, University Press. p. 218. ↩

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (London: Murray, 1859) p.449. ↩

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (London: Murray, 1859) p.449. ↩